|

| Weihui People’s Court. Image credit: Weihui People’s Court Official WeChat account |

The 2021 prosecution of a young man surnamed Li for forming a “People’s Party,” disseminating writings prosecutors deemed “slanderous,” and seeking to recruit members points to an increasingly prevalent tactic of criminalization – a shift from charging political dissidents with endangering state security (ESS) crimes to instead charging them with “picking quarrels and provoking trouble.” Over a decade ago, the same acts of disseminating “reactionary,” “subversive,” or “slanderous” articles in the name of a political party would have been more likely punished as ESS crimes.

In Part I, Dui Hua detailed Li’s case and the court's rationale for charging him with “picking quarrels and provoking trouble.” This entry looks at similar cases and shifts in sentencing, considering reasons for the enhanced usage of “picking quarrels and provoking trouble.”

People's Parties

Li’s People’s Party was not the first political party of its kind. Dissident intellectuals, farmers, workers, and Communist idealists have recruited like-minded individuals and organized underground groups over the past two decades. They often choose names like “People’s Party,” mindang or renmindang, as a way of invoking public support or positioning themselves as representatives of the Chinese people. These “People’s Parties” do not appear to be connected to each other; rather their appeal is to specific social groups. While some aspire to Western-style democracy and call for a multiparty political system, others believe that a return to pre-reform era socialism is a panacea for social injustices and government corruption.

Dui Hua previously reported that around 2008, Dong Zhanyi (董占义) founded a different People’s Party, which was later renamed to “New Era Communist Party of China.” Dong was convicted of subversion and contract fraud in October 2011 and was sentenced to life in prison. Another party founder Chen Guohua (陈国华) was given a 14-year prison sentence for subversion. This party, once active in Beijing, Henan, Shandong, and Jiangxi, aimed to fight corruption and allegedly recruited aggrieved workers and petitioners to overthrow the Chinese Communist Party.

Another opposition group, which also existed online like Li’s party, was called the People’s Party. In November 2009, news media sources reported that a Henan netizen surnamed Yan stood trial in Wuhan for inciting subversion after proclaiming himself to be chairman of the “Chinese People’s Party” (中国人民党). Yan’s political orientation is ambiguous. Dui Hua learned that his full name is Yan Bianfang (阎边防). Yan reportedly wrote two “subversive” articles and read them aloud in a video he posted on a US website. The links to his articles and video were circulated domestically on Chinese websites. Yan was sentenced to one year in prison and completed his prison sentence in April 2010. Yan was charged with inciting subversion, a crime of endangering state security; Li’s crime and sentencing were similar to Yan’s, but in an apparent shift in practice, Yan was charged with “picking quarrels and provoking trouble.”

The reason behind this shift is unclear, but it might be a way to obscure cases of a political nature that would otherwise attract scrutiny by treating them as pocket crimes, like “picking quarrels and provoking trouble.” Crimes of “picking quarrels and provoking trouble” are tried in district courts while ESS crimes are tried in intermediate courts. District court trials tend to be quicker and attract less attention than those at the intermediate level. Judges are typically less experienced, and corruption is more prevalent. The comparative lack of attention means that judgments are less contentious, with the rationale behind them drawing less scrutiny.

Another possible explanation for the shift might be that the procuratorate or the court thinks it is easier to determine that a post or act caused “social harm” or “disturbed the social order” than it is to show the “subversion of state power.” The threshold for justifying pocket crimes is lower than that for ESS charges. This catch-all crime now carries a maximum prison sentence of 10 years, up from the previous cap of five years, following the eighth amendment to the Criminal Law in 2011.

|

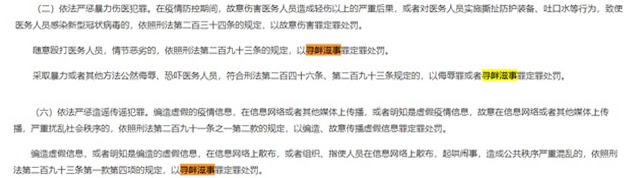

| Excerpts from the joint notice broadening the application of the crime of picking quarrels and provoking trouble to include Covid-related actions. Image credit: Ministry of Public Security of China |

Since the outbreak of COVID-19, “picking quarrels and provoking trouble” has been used along with an array of other criminal offenses to curb so-called “pandemic-related crimes.” On February 10, 2020, two months into the pandemic, a notice jointly issued by the Supreme People’s Court, Supreme People’s Procuratorate, Ministry of Public Security, and Ministry of Justice broadened the crime’s application to punish those who cause chaos by using “violence or other means” to insult or intimidate medical personnel, as well as those who spread “false news” or “rumors” about the pandemic.

By February 25, 2020, about a month after Wuhan was first placed on lockdown, the Supreme People’s Procuratorate reported handling 301 pandemic-related picking quarrels cases nationwide involving 375 people. In addition to citizen journalists, street protesters, and rights lawyers, Li’s case indicated that dissident party organizers were also among those at risk of arrest for this pocket crime.

The vague definition of Article 293 has long attracted criticism from China’s legal scholars and experts. Prominent lawyer Zhu Zhengfu recently suggested in an interview with China News Weekly that the government “abolish the crime of picking quarrels and provoking troubles at a right time.” Zhu, a representative of the Consultative Conference and a member of the All China Lawyers Association’s supervisory board, pointed out that “clarity is the essential requirement of the Nulla poena sine lege; however, the wording in the Article 293 is excessively vague, such as ‘at will,’ ‘willfully,’ ‘serious circumstances,’ or ‘causing serious disturbances to public order.’ Yet those described [activities] are the key elements of the crime.”

|

| News coverage featuring excerpts of Zhu’s statements on Article 293. Image credit: China News Weekly via Weibo |

Zhu, whose comments came during preparation for the “Two Meetings” which began March 4, added that the definition’s ambiguity enables authorities to selectively enforce the law and harmed citizens’ rights. Zhu’s suggestion has since been echoed by others. Xiao Shenfang, a member of the NPC and vice chairperson of the All China Lawyers Association, also plans to submit a similar proposal at the “Two Meetings.” Xiao also warned of the law’s over-criminalization of social issues.