Read Part I here.

|

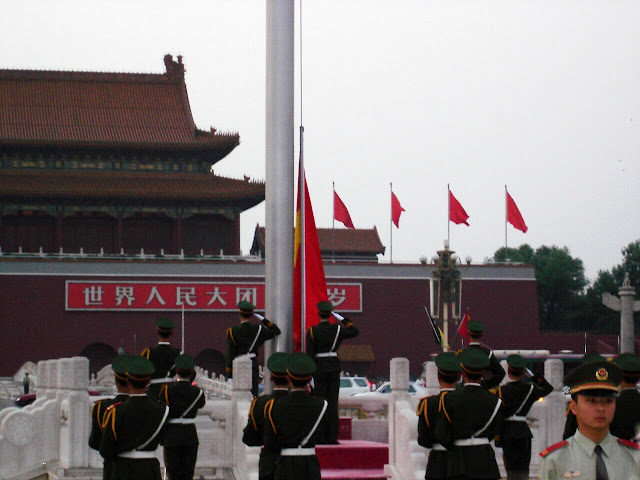

| A flag hoisting ceremony in Tiananmen Square in 2005. Image credit: 武当山人 / CC BY-SA 3.0 |

The desecration of national symbols is a crime under Chinese law. The National Flag Law was enacted in June 1990 and was extended to cover the national emblem one year later. While the laws were merely codes governing formalities to display the national symbols, a provision to the 1979 Criminal Law added in 1990 made intentionally desecrating the national flag and symbol in public a crime punishable by up to three years’ imprisonment.

This article explores the often-ignored topic of flag desecration in China. Part I looked at trends in sentencing and the law’s application across different cases. Part II discusses how the law is applied to different groups like Falun Gong, Tibetans, and Uyghurs. While most publicly disclosed cases involve “ordinary” offenders who did not desecrate the flag for political reasons, the same acts committed by practitioners of Falun Gong and ethnic minorities tend to result in lengthier prison sentences.

Political Cases

In cases where national symbols in China are desecrated in protest of public policy, like those of Wang Chunhua (王春花) and Lie Jinjie (刘杰津) discussed in Part I, the starting point for sentencing appears to get noticeably longer. Two other cases, which involved criticism of the CCP and so-called “anti-China elements,” also resulted in lengthier prison sentences. However, the circumstances of these cases have not been made entirely clear in available sources.

- Tianjin’s first flag desecration case concerned Wu Zhaoming (吴兆明), who was sentenced to two years in prison in December 2017 for cutting up and damaging a total of 66 national flags, allegedly in a bid to express his discontent with the CCP. Some of the damaged flags and flagpoles were found in garbage bins and on sideroads. Available sources did not explain why Wu became dissatisfied with the CCP.

- In a separate case in Changsha, Hunan, Wu Di (吴迪) was sentenced to 18 months in prison in January 2020 for setting fire to four flags with a lighter. Prosecutors alleged that Wu experienced depression due to unemployment and became “thrill-seeking” after he browsed overseas “anti-China” websites. From October 1-2, the 70th anniversary of the People’s Republic of China, he circulated a video to his friends of himself burning the flags on a university campus.

Falun Gong

As shown in the chart below, from 1998-2016, only five people had received the maximum sentences of three years in prison. Of them, Dui Hua found that two were Falun Gong practitioners:

Chart 1. Sentencing breakdown of defendants convicted of Article 299

|

| Source: Records of People’s Court Historical Judicial Statistics: 1949-2016 |

|

| The Tibetan flag carried during Olympic torch run demonstrations in San Francisco, California, on April 9, 2008. Image credit: Victor Lee / CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 |

- Around 2011, Sonam Norgye received a three-year prison sentence in Basu [Pashoe] County, Tibet, for hauling down and soiling with feces a Chinese flag that had been raised by government workers in the area;

- In September 2013, a court in Sichuan’s Kardze County reportedly handed prison terms of between one and four years to three monks accused of pulling down the Chinese national flag at a local school. Because Article 299 only carries a maximum sentence of three years, one of the monks might have been convicted of an additional crime.

|

| A picture of Jama Mosque in Kargilik County, Kashgar, with China's flag and propaganda banners that read "Love the Party, Love the Country." The photo is undated but was published by Radio Free America (RFA) in August 2018. Image credit: RFA via an unnamed RFA listener |

- On February 20, 2013, two Uyghurs were sentenced to 24-30 months’ imprisonment in Wensu County, Aksu Prefecture. State news media sources claimed that they refused to perform salah, the obligatory Muslim prayers which are performed five times each day, in mosques where the national flag was displayed. They pulled down and burned the Chinese national flag on December 26, 2012.

This trial was attended by a total of 1,208 people, including county congress representatives, religious figures, and villagers. The large size of the court audience suggested that the trial was conducted in the form of a public sentencing rally, which is often held in large outdoor public spaces like plazas and stadiums where the accused are bound and flanked by police in front of crowds of spectators that can number in the thousands. While public sentencing rallies in Xinjiang are typically held in cases involving violence, drugs, and state security, this case indicates that Uyghurs in flag desecration cases can also be brought to a public rally.

- Just a month after the flag desecration case in Wensu County, a similar case was concluded in Awat County, also in Aksu Prefecture. According to news media sources, all mosques in the county were required to fly the Chinese national flag after August 2011. A muezzin (the person who performs the call to prayer) put the flag into a fireplace; he blamed the flag for the drop in mosque worshippers. Concerned about the choking smoke, he threw the half-burned flag outside of the mosque. He received a 30-month prison sentence on March 19, 2013.

It is worth noting that the scope of activities punishable under Article 299 is expanding. The tenth amendment to the Criminal Law, which went into force in November 2017, made insults to the national anthem a crime punishable under the same article. Dui Hua previously reported the first known such case involving a female member of Almighty God in Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps. She received a 30-month prison sentence for composing “the Song of Satan’s Victory,” similar in tune to the national anthem.

Effective March 1, 2021, a new provision added to Article 299 extended the same punishment to those who “misrepresent, defame, profane or deny the deeds and spirits of heroes and martyrs.” On the same day, Chinese blogger Qiu Ziming (仇子明) became the first person to be convicted of this new crime over his posts that authorities say demeaned the Chinese military casualties of a border clash with Indian soldiers in June 2020. Qiu, also a victim of China’s practice of airing forced confessions on state television, is serving his eight months’ prison sentence in Jiangsu until October 19, 2021.

|

| Footage of Qiu's televised forced confession. Image credit: Hanqiu.com |